Back in the day, when I was young and setting out on a pre-med course at the University of Michigan, I gravitated toward the sciences. I was even pretty good at the stuff, if the grades I received were any indication. In fact, very good. I routinely received the top grade in a huge freshman lecture course in chemistry.

I remember taking a physics course as well that year; even though I never attended a single lecture — they were held at the completely unreasonable hour of 8:00 am, after all — and I studied for only a day or two before the final exam. Still, I managed to receive an A. (Only later did problems emerge when I was forced to enter chemistry and zoology lab, where I proved to be a first-class klutz.) You might think that this would indicate an ability on my part to understand at least a little of physics today. And I even have a top-notch Italian physicist available here to explain it all to me.

No such luck.

Physics today is not what it used to be

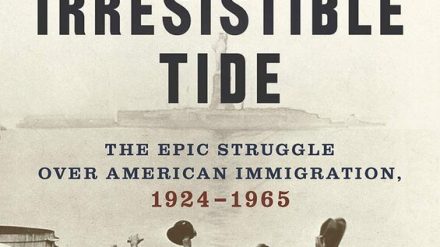

Now here comes Carlo Rovelli with a bestselling book titled Seven Brief Lessons on Physics. Compiled from a series of newspaper columns in his native Italy, the book was such a breakaway bestseller there that it even outsold the Shades of Gray novels! It’s tiny, the length of a novella — 96 pages in its American hardcover edition — so the book is meant to be read (and presumably understood) at a single sitting.

Seven Brief Lessons on Physics by Carlo Rovelli ★★★★☆

The “Lessons” describe six principal milestones in twentieth-century physics. This is Rovelli’s attempt to put contemporary physics in context. He places our growing understanding of the physical universe on a continuum that started when the Greeks first brought intellectual firepower to bear on the biggest questions humankind can ask. Individual chapters cover Relativity Theory, Quantum Theory, cosmology, particle physics, the clash between relativity and quantum mechanics, and the character of black holes. A seventh chapter deals with “Ourselves,” an often poetic effort to dissect the meaning of all this learning for our lives as individuals and as a civilization.

“Seven Lessons” meant to explain may only confuse

Enough has been written about the topic of relativity that it’s possible for an educated reader to know the rudiments of the theory. Understanding it is something else. After all, what does it mean that space and time are curved? Beats me.

Quantum mechanics are even more impenetrable for a layperson — at least, this layperson — to grasp. A popular version of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle is familiar, of course — but just try to understand what even that really means, let alone the original version, which is impenetrable. Taken to its logical conclusion, “reality is only interaction,” as Rovelli explains. Come again?

When I studied physics and chemistry more than half a century ago, I was taught that protons, electrons, and neutrons were the basic building-blocks of the atoms that had previously been thought to be the fundamental particles of all matter. Now physics teaches us that “electrons, quarks, photons, and gluons are the [even tinier] components of everything that sways in the space around us” — not to mention our own bodies. Here’s Rovelli again: “Quantum mechanics and experiments with particles have taught us that the world is a continuous, restless swarming of things, a continuous coming to light and disappearance of ephemeral entities. A set of vibrations, as in the switched-on hippie world of the 1960s. A world of happenings, not of things.” Does that make it all any clearer?

A paradox at the heart of our understanding

Just in case you think this all fits together into a neat picture of the physical reality we all experience, listen: “There’s a paradox at the heart of our understanding of the physical world. The twentieth century gave us the two gems of . . . general relativity and quantum mechanics.” These two theories lie at the base of all our understanding today. “And yet the two theories cannot both be right, at least in their current forms, because they contradict each other.” Rovelli himself is an advocate of one of several current theories that attempt to close the gap between general relativity and quantum mechanics. It’s called “loop quantum gravity theory.” And, even after Rovelli’s attempt to explain it in practical terms, it makes absolutely no sense whatsoever to my untutored mind.

A recurring theme in Seven Lessons is that reality isn’t what it appears to be, so far as physicists are concerned. For example, “due to the limitations of our consciousness we perceive only a blurred vision of the world and live in time. To borrow words from my Italian editor, ‘what’s non-apparent is much vaster than what’s apparent.'”

Bringing the argument down to Earth

Rovelli is at best when he brings his argument down to Earth, so to speak. “When we say that we are free,” he writes, “and it’s true that we can be, this means that how we behave is determined by what happens within us, within the brain, and not by external factors. To be free doesn’t mean that our behavior is not determined by the laws of nature.

“It means that it is determined by the laws of nature acting in our brains. . . Our moral values, our emotions, our loves are no less real for being part of nature, for being shared with the animal world, or for being determined by the evolution that our species has undergone over millions of years. . . Our reality is tears and laughter, gratitude and altruism, loyalty and betrayal, the past that haunts us and serenity.

“Our reality is made up of our societies, of the emotion inspired by music, of the rich intertwined networks of the common knowledge that we have constructed together. All of this is part of the self-same ‘nature’ that we are describing.”

In other words, reality is what we make of it, physics be damned.

About the author

The Italian theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli currently works in France. He specializes in the field of “quantum gravity” and is one of the founders of a theory that attempts to reconcile general relativity with quantum mechanics.

For more good reading

You might also enjoy Science explained in 10 excellent popular books.

If you enjoy reading nonfiction in general, you might also enjoy:

- Great biographies I’ve reviewed: my 10 favorites

- My 10 favorite books about business history

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.