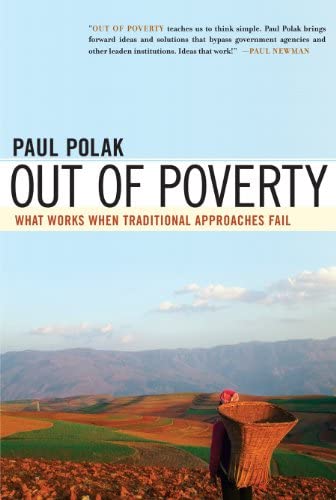

When F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote “the very rich are different from you and me,” he was referring to their attitudes and beliefs, not to the way they conduct themselves in business or politics. But he might very well have gone on to observe that great wealth carries with it considerable power that enables the very rich to have their way no matter how badly they act. In The Profiteers: Bechtel and the Men Who Built the World, Sally Denton illustrates just how much power the world’s largest construction firm has wielded both in business and in politics, proving itself virtually untouchable by the law.

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

The colossus that is Bechtel

Bechtel is a privately owned global company headquartered in San Francisco. In 2015, the company ranked #5 on the Forbes list of America’s largest private companies, with annual revenue of $37 billion. Like the Koch Brothers’ family firm, Koch Industries (#2 on the Forbes list), Bechtel operates outside the scrutiny of financial regulators, so what it says about itself is often difficult to confirm. The firm advertises itself on its web site as having 55,400 employees who have completed 25,000 projects in 160 countries on 7 continents. All that may be true, or at least within reasonable range of the truth. But, as Denton demonstrates in her eye-opening study, much of what the notoriously secretive company says about its history and the way it conducts its affairs is highly questionable.

The Profiteers: Bechtel and the Men Who Built the World by Sally Denton ★★★★☆

A fifth-generation member of the family, Brendan Bechtel, now serves as President and Chief Operating Officer. (An outsider is CEO.) The company traces its beginning to 1898 when Brendan’s great-great grandfather, Warren Bechtel, began constructing railroads in the Oklahoma Territory with a team of mules. However, the company didn’t rise to national prominence until the Great Depression, when it was one of the so-called Six Companies (twelve, in reality) in the consortium that built the gargantuan Hoover Dam. In World War II, without prior experience in shipbuilding, Bechtel’s shipyards turned out 560 ships under a U.S. government contract, earning enormous profits. But Bechtel didn’t embark on a truly global course and set the stage for raking in billions of dollars in profits until Brendan’s grandfather, Steven D. Bechtel, Jr., took up the reins in 1960 and recruited John A. McCone as a virtual partner.

Bechtel and McCone collaborated in inventing two new business concepts: the “turnkey” project and the now-notorious device of “cost-plus” government contracts. The latter helped to make both of them fabulously rich once the floodgates opened with the inauguration of Richard Nixon as President in 1969. The arrangement guaranteed that the company would realize a profit — and provided an incentive for cost overruns, since its profit was calculated as a percentage of the total cost! (After working for and with Steve Bechtel, McCone shifted to a career in government, which culminated with his appointment in 1961 as CIA Director. Over several decades in government service, McCone frequently used his influence in support of his former company: apparently, he continued to hold a share of ownership.)

Conservative politics in the light of reality

From its earliest days, the senior leadership of Bechtel has favored right-wing politics, inveighing against “communism” and government regulation. Each successive generation of Bechtels has “advocated a consolidated, free-wheeling capitalistic economy unrestrained by government oversight or taxation.” Astonishingly, on one occasion, writing in the journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Steve Jr. claimed that “the U.S. government has not had a major role in the success of our business.”

In reality, however, as Denton emphasizes, “the Bechtel family owes its entire fortune to the US government.” Bechtel was built and continues to flourish on the basis of enormous government contracts. Because the firm is private, there is no way to learn how much of its business comes from government agencies, both domestic and foreign. However, given the spectacular size of nearly all the projects it manages, government funding must figure in the overwhelming majority.

Every one of its signature projects was a multi-billion-dollar undertaking: the Hoover Dam, shipbuilding in World War II, the Trans-Arabian Pipeline, the Bay Area’s BART system, the city of Jubail in Saudi Arabia, the “Chunnel” under the English Channel, Boston’s Big Dig, 35,000 trailers after Hurricane Katrina, the Hong Kong airport, the US Embassy in Baghdad (the world’s largest), rebuilding Iraq’s infrastructure, and managing the U.S. nuclear arsenal and national nuclear research labs. These and many other Bechtel jobs were built with billions in government funds.

Deeply involved in intelligence operations

In the 1940s, Bechtel became enmeshed in overseas US intelligence operations. “The company so mirrored the CIA by participating in intelligence gathering and providing cover to CIA agents,” Denton writes, “that it was widely considered a government surrogate, if not a full-fledged government enterprise by both the political leaders of the countries in which it operated, as well as by its rivals in industry. . . [I]t was often difficult to determine if Bechtel Corporation was doing favors for the US government, or if it was the other way around.”

As a result of the close, ongoing relationship between the company and the US government and the enormous influence wielded by the firm, Bechtel was repeatedly able to avoid being held responsible “for its cost overruns, unfair employment practices, security violations, pattern of retaliation against whistleblowers, and massive reductions in its workforce.” The company might also have been disgraced (but wasn’t) by the blatant conflicts of interest that arose from the actions of John McCone, George Schultz, and Casper Weinberger to steer business its way from their senior posts in Washington, DC. (Schultz was Secretary of State, Weinberger Secretary of Defense.)

“In the end,” Denton concludes, “this is the ugly, untold story of America. A story not of the triumph of laissez faire capitalism, but of Profiteers whose sole client was government itself.”

The curious case of Jonathan Pollard

Denton begins and ends her story of Bechtel with the case of Jonathan Pollard, a former intelligence analyst who was convicted of spying for Israel in 1987 and released from prison only in 2015. The median penalty for his offense was a term of between two and four years in prison, and since Pollard expressed remorse and entered into a plea agreement with the government, he was set to be sentenced to time served. Instead, heeding a secret letter from Casper Weinberger, the former Bechtel executive who was serving as Secretary of Defense, the judge sentenced Pollard to life.

Denton contends that Pollard’s life sentence came about because Weinberger feared exposure for his part in Bechtel’s secret involvement in building a nuclear reactor in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq (the one subsequently bombed by Israeli planes). Though this makes for a good story, it’s impossible to believe. Generations of senior government officials, few of them beholden to Bechtel, have repeatedly weighed in against clemency for Pollard.

A long list of security breaches

In supporting their case, they have cited a long list of serious breaches of US security. For example, they have alleged that he turned over to Israel “the National Security Agency’s ten-volume manual on how the U.S. gathers its signal intelligence, and disclosed the names of thousands of people who had cooperated with U.S. intelligence agencies.” They have also insisted that Pollard didn’t spy just for Israel, as his apologists contend, but “shopped” secret documents to other countries, including Pakistan.

Although I am congenitally skeptical of statements from senior government officials, especially those from the military-intelligence establishment, it defies logic for me to believe that so many prominent figures in the federal government over such a long period of time could be making all this up and repeating it year after year after year. There’s simply too much credible detail in their claims. Denton’s implied rejection of the case against Pollard undermines the credibility of her story — most unfortunately, since her account of Bechtel’s history otherwise squares with historical fact in every respect known to me.

About the author

The Nevada-based investigative journalist Sally Denton has written eight books about such diverse subjects as pioneer women in the American West, the growth of Las Vegas, the life of Helen Gahagan Douglas, and the rise of the American Right.

For related reading

Like to read books about business? Check out My 10 favorite books about business history.

If you enjoy reading nonfiction in general, you might also enjoy:

- Science explained in 10 excellent popular books

- 10 great biographies

- Top 10 nonfiction books about politics

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.