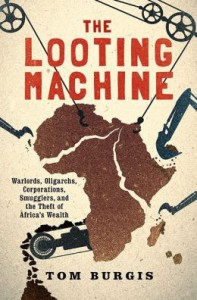

Misconceptions abound in the public perception of corruption in Africa. Tom Burgis’ incisive new analysis of corruption on the continent, The Looting Machine, dispels these dangerous myths.

For starters, corruption is mistakenly believed to reign supreme in every country on the African continent. (There are 48 nations in Sub-Saharan Africa, with a combined population of more than 800 million.) Of course, it’s true that some African countries rank very low on Transparency International’s “Corruption Perceptions Index” (CPI) — after all, Somalia merits the very lowest score, with Sudan and South Sudan not far above it — but only Eritrea and Guinea-Bissau rank at all close to them. In between them are many other countries: Middle Eastern, Central Asian, Caribbean, South Asian. And three Sub-Saharan African nations rank in the top third of the 175 countries in the CPI: Lesotho, Namibia, and Rwanda, with Ghana close behind. Ghana scores better than Greece, Italy, and several other European nations.

Second, corruption in Africa is viewed as intractable. It’s widely believed that nothing can be done about it. Nonsense! One of the largest and most potent sources of the cash that fuels corruption is foreign aid. Institutions like the World Bank, USAID, and other national and international agencies direct most, if not all, their support to governments. This, despite the obvious evidence on the ground that a huge proportion of this aid goes straight into the pockets of the ruling elites. If foreign aid were doled out more selectively to community-based organizations, local agencies, and NGOs with grassroots operations, the picture might be very different. As things stand, only a trickle of foreign aid gets to the people who need it most: the poor.

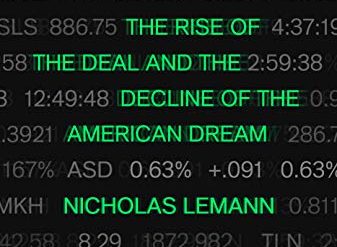

The Looting Machine: Warlords, Oligarchs, Corporations, Smugglers, and the Theft of Africa’s Wealth by Tom Burgis (2016) 354 pages ★★★★★

Lastly, and most significantly, too many observers characterize African corruption as a uniquely African phenomenon that grows out of ethnic rivalries and the failure of European colonists to establish stable native governments. Those factors, while present, are only part of the story. Equally, if not more, consequential is the role of foreign investment — principally from China, the US, and Western Europe — in exploiting the continent’s abundant resources, often paying through the nose for the privilege.

Corruption is a two-way street: briber and bribee need each other. And those Western investors include some of the world’s biggest US- and European-based multinational corporations — most prominently, Big Oil and the major mining companies. Chinese companies are even worse because they’re not constrained by legal restrictions at home. Prominent foreign aid cheerleaders like Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University do the African people no favors by advocating huge increases in official aid, rationalizing that some of it will actually do good. Just ask the first ten Africans you meet on the street in Lagos or Nairobi or Luanda. Unless you happen to run into a member of the privileged elite, you’ll get an earful about Western-enabled corruption.

Spotlighting the two-way street of corruption

The Looting Machine spotlights this two-way street, with an emphasis on commerce. The role of foreign aid receives little attention. The principal source of corruption in Africa, Burgis contends again and again, is its wealth of natural resources: oil, gas, gold, diamonds, copper, iron, and many other materials essential to the rich nations’ consumer economies. Citing an analysis by McKinsey, he reports that “69 percent of people in extreme poverty live in countries where oil, gas, and minerals play a dominant role in the economy and that average incomes in those countries are overwhelmingly below the global average.” This is one of the most tragic consequences of what economists refer to as the “resource curse.” Burgis asserts that “An economy based on a central pot of resource revenue is a recipe for ‘big man’ politics.”

It’s no accident that the resource curse finds its fullest expression in Africa: the continent accounts for 13 percent of the world’s population and just 2 percent of its cumulative gross domestic product, but it is the repository of 15 percent of the planet’s crude oil reserves, 40 percent of its gold, and 80 percent of its platinum — and that is probably an underestimate.”

The scope of the corruption this cornucopia of resources makes possible is difficult to comprehend. For example, “When the International Monetary Fund examined Angola’s national accounts in 2011, it found that between 2007 and 2010 $32 billion had gone missing.” That’s billion with a “B.” And this, in a country of just 21 million people — a population roughly equivalent to that of Sao Paulo, Seoul, or Mumbai.

If you want to gain perspective on poverty, war, and corruption in Africa, read this book.

The emphasis in The Looting Machine is on those countries Burgis knows well: Angola, Nigeria, Congo, with less intensive reporting from several other nations.

About the author

Tom Burgis has worked for the Financial Times in Africa since 2006, covering business, politics, corruption, and conflict. On his LinkedIn page, he describes his reporting as encompassing “Oil, mining, terrorism, the arms trade, corporate misconduct, intelligence, money-laundering, the underbelly of the global economy, forgotten war zones, tales of the human soul.” He is currently the Investigations Correspondent for the Financial Times, no longer limited to Africa.

For more reading

This is one of 20 top books about Africa, including both fiction and nonfiction.

This is also one of the books I’ve included in my post, Gaining a global perspective on the world around us.

Like to read books about politics and current affairs? Check out Top 10 nonfiction books about politics.

If you enjoy reading nonfiction in general, you might also enjoy:

- Science explained in 10 excellent popular books

- Great biographies I’ve reviewed: my 10 favorites

- My 10 favorite books about business history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.