Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

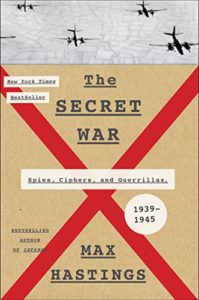

Shelves-full of history books have been written about the triumphs of Allied intelligence in World War II. The Ultra Secret. The Man Who Never Was. Operation Mincemeat. Agent Zigag. Double Cross. A Man Called Intrepid. I’ve read all these and many more. (There are hundreds.) Now comes British journalist and historian Max Hastings with a revisionist view in The Secret War. With his eyes focused on the harsh realities of that all-consuming conflict, Hastings debunks the myths that inspired these books and takes their exaggerations down a peg with a long-lacking sense of perspective. The effect is sobering. This is revisionist history at its best. Anyone who seeks to understand how World War II was really waged should read this book without delay.

Revisionist history: myths debunked

Hastings reviews some of the many fanciful reports that have come out over the years about British and American espionage in World War II. For example, he savages William Stevenson’s self-aggrandizing tale in A Man Called Intrepid, calling the book “wildly fanciful.” Among the more obvious lies in Stevenson’s book is the fact that no one but he himself ever called himself Intrepid. And, as Hastings makes clear, Stevenson’s work coordinating British intelligence in the United States had virtually no impact whatsoever on the war.

He is less harsh in his oblique references to other books, but he makes clear that the many bestselling titles exaggerate the importance of the spies they made famous. Even the legendary Alan Turing comes under the microscope: Hastings asserts that another young mathematical genius who also worked at Bletchley Park was equally important in cracking the Enigma Code. More significantly, that celebrated breakthrough itself made less of a contribution to the Allied victory than other successes in deciphering Axis codes. (He cites in particular the German and Japanese naval codes.) “Bletchley was an increasingly important weapon,” Hastings notes, “but it was not a magic sword.”

The Secret War: Spies, Ciphers, and Guerrillas, 1939-1945 by Max Hastings (2016) 645 pages ★★★★★

Signals versus human intelligence

The overarching theme in The Secret War is the primacy of signals intelligence. Hastings contends that breakthroughs in deciphering codes by the British, Russians, and Americans contributed far more decisively to the successful outcome of the war than any missions undertaken by spies. And, except in Russia from 1943 onward, the efforts of Resistance movements in Europe were even less significant (although they played a large role in fostering popular morale). There is one possible exception, the work of the improbably colorful agents portrayed in Ben McIntyre’s Double Cross: The True Story of the D-Day Spies. But even this undeniable success story has to be tempered by the realization that signals intelligence played a large role in setting up and supporting the operation. On all sides, enormous numbers of people were engaged in listening to, decoding, interpreting, and reporting on intelligence gained by radio.

However, “One of the themes in this book is that the signals intelligence war, certainly in its early stages, was less lopsided in the Allies’ favor than popular mythology suggests.”

How much did secret intelligence actually contribute to the war’s outcome?

Viewing the big picture, Hastings is skeptical about the effectiveness of intelligence of any sort. As he notes, “Perhaps one-thousandth of 1 per cent of material garnered from secret sources by all the belligerents in World War II contributed to changing battlefield outcomes.” In the course of The Secret War, he cites just four strategically significant battles where intelligence turned the tide: the North Atlantic war under the sea, the American victory over the Japanese at Midway, the unexpected Russian offensive at Kursk, and the misdirection about the Allied landing at Normandy rather than the Pas de Calais.

Viewed from 30,000 feet and the passage of more than seventy years, “nowhere in the world was intelligence wisely managed and accessed.” Though Stalin and Hitler were both notoriously disdainful of secret intelligence, as was the Japanese military, the Americans and the British also failed to make genuinely effective use of the information turned up by their spies and code-breakers.

Other revelations

Perhaps understandably, in writing about Allied intelligence in the war, American and British authors have focused on the work of MI6, MI5, the OSS, and the enormous team of academics at Bletchley Park. However, Hastings makes clear that the Soviet Union was far more successful in uncovering actionable espionage than either of its chief Western Allies. “Some Russian deceptions,” he writes, “dwarf those of the British and Americans.” Hastings’ account of Stalin’s intelligence operations is particularly revealing. So, too, is his skeptical exploration of both German and Japanese secret intelligence. The FBI also comes under fire: “All intelligence services seek to promote factional interests and inflate their own achievements, but the wartime FBI carried this practice to manic lengths . . . The FBI’s incompetence was astonishing.”

About the author

Max Hastings is a prominent British journalist, editor, historian, and author. He has served as editor-in-chief of the Daily Standard and The Daily Telegraph and has presented historical documentaries on the BBC.

For related reading

This is one of the 10 top WWII books about espionage.

I’ve also reviewed two of the author’s other excellent WWII histories: Operation Chastise: The RAF’s Most Brilliant Attack of World War II (Bomber Command’s most successful attack on Nazi Germany was not on its cities) and Das Reich: The March of the 2nd SS Panzer Division Through France, June 1944 (Down in the weeds with the French Resistance).

You’ll find this book listed on my post, 10 top nonfiction books about World War II.

For stories about the Resistance efforts Hastings thinks were ineffective, see 10 true-life accounts of anti-Nazi resistance .

Geniuses at War: Bletchley Park, Colossus, and the Dawn of the Digital Age by David A. Price (The top-secret story of the first digital computer) explores some of the critical themes in the Hastings book. So does Bletchley Park and D-Day: The Untold Story of How the Battle for Normandy Was Won by David Kenyon (How Bletchley Park helped the Allies win on D-Day).

Check out The 10 most consequential events of World War II and Good books about the Holocaust.

You may enjoy browsing through The 10 best novels about World War II and 20 top nonfiction books about history.

If you’re looking for a broader view of human history, check out New perspectives on world history.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.